Introducing 'alumni unabridged' - our long-form profile series that goes beyond the soundbite. These are in-depth narratives that explore the lives, careers, and reflections of our alumni. Each feature offers a deeper look into the paths they've taken and the mark they continue to make on the world.

As her eponymous ceramics company celebrates its 40th anniversary, Bedford College alumna Dame Emma Bridgewater speaks to Jessica Jonzen about the social purpose at the heart of her business, her thoughts on AI, and why she’ll never retire.

In the story of British craft and entrepreneurial flair, few contemporary names have become as warmly embedded in the national imagination as that of Emma Bridgewater. Her polka dot mugs, sponge-painted bowls and crockery baring slogans such as ‘Muddy Walks’ and ‘Fish & Chips by the Sea – Rain Likely’ have not only filled kitchens across the UK but helped reframe the idea of domestic ceramics.

Emma Bridgewater pieces are both utilitarian and romantic, objects with emotional heft as well as practical usefulness and a uniquely British sensibility. But they are about more than nostalgia. Made in the heart of the Potteries in the Emma Bridgewater factory in Stoke-on-Trent, each piece represents her steadfast commitment to British manufacturing, to safeguarding skills which have been handed down through generations, and prioritising people over profit margins.

As her eponymous pottery brand marks its 40th anniversary, Emma Bridgewater – now Dame Emma Bridgewater, having received a damehood in the King’s Birthday Honours earlier this year – remains thoughtful and candid about the journey that brought her here – and the serendipitous mix of purpose, timing and consequence that shaped it.

When she first alighted on the idea for her business at the age of just 23, Dame Emma was simply trying to find a present for her mother. “I wanted to buy her a nice mug and couldn’t see anything that spoke to the way she and her friends were now living their lives,” she says. “Women had left the whole faff of formal life behind – they didn’t have to polish their mahogany dining tables anymore – but the china industry hadn’t worked that out. Everything was either very utilitarian or dainty wedding china.”

She had a very clear vision: “I had an oddly powerful image in my mind of a sunlit dresser with lovely mismatched, hand decorated colourful pottery on it. It was a sort of dream version of the dresser in my mum’s kitchen. I wasn’t a designer but once I sat down to it, I could draw all the shapes and had a very clear idea of what I wanted.”

Dame Emma was advised to go to Stoke-on-Trent, regarded as the world capital of ceramics, and which had suffered greatly through post-industrial politics. “When I got off the train in Stoke in the late summer of 1984, I realised I’d never been to the Midlands. I had a series of revelations of shame that I didn’t know about the post-industrial chaos that was very evident there,” she says.

“What was tumbling down was a whole way of life. The skills and traditions that had been accrued over generations through sweat and tears were being slung aside and I couldn’t believe it. I really felt ‘somebody’s got to do something about this.’ It just felt so wasteful.” She knew that the pieces she wanted to create had to be produced there. “Stoke, and the people there, gave me a sense of wanting to be a particular kind of employer who values what they have to offer.”

Her early impulse, at once personal and practical, has reinvigorated the Potteries and Emma Bridgewater is one of Stoke-on-Trent’s most significant manufacturing success stories, providing jobs for local people and attracting visitors to its cheerful factory in Hanley. “I’ve employed mothers and daughters, fathers and sons. The business is all about people and I'm really concerned always to make sure the studio is designing in a very personal way, that they’re not thinking about the market but of our customers as people with real lives,” says Dame Emma.

The company’s status as a certified B Corp is perhaps the clearest symbol of her commitment to social responsibility. “I am quite Quakerish in my outlook and feel that the idea of B Corp is old, not new. Businesses used to be much more aware of the community in which they did their business, regarding themselves as part of it,” she says. “Gaining – and keeping – your B Corp status means good practices become enshrined in the business, rather than flowing out when people come and go. We became a B Corp because we are an ethical company, not to become one.”

That moral seriousness has never come at the expense of humour or charm. Quite the opposite. Emma Bridgewater’s ceramics have long balanced nostalgia and wit, celebrating the quiet joys of domestic life – pleasures she associates with the warm, creative world her mother, Charlotte Stroud, fostered in their rambling North Oxford home. That legacy became all the more poignant after a riding accident in 1991 left her mother severely brain-damaged and unable to care for herself until her death in 2013. The business, Dame Emma says, became “absolutely an homage” to her. It is one thread in a tapestry of familial creativity: Charlotte was also mother to two other intensely creative daughters – the late Nell Gifford, co-founder of Giffords Circus, and the writer and bestselling author Clover Stroud.

That shared impulse – to rescue, restore and reimagine – was clearly planted early. “Nell and I never talked about the glaring similarity there was between her extraordinary circus career and my weird adventure in the pottery business, in that we both saw something that we couldn't bear to let die and doing something apparently completely impossible. Both were Herculean labours, and I feel quite sorry for the younger us when I look back,” she laughs.

Four decades on, Dame Emma has entered a new chapter of her own. Now 63, she has recently stepped away from any day to day involvement in the management of Emma Bridgewater and now serves as Founder, Board Director, mentor to the creative teams and cheerleader for the brand, having sold a stake in the business – a transition which she admits has been challenging. “It’s difficult but none of my children wanted to take it on when the time came to make that decision. But it was also clear to me that this was a crazy adventure that I had set out for myself, and I didn’t want any of them to feel bidden to do it.”

Yet retirement, she insists, is not on the table. “I think that when you retire you stop participating – you may think you’re still in the world but you’re not: you’re a spectator, you got off the bus,” she says. “You're not obeying the exigencies of an organisation or a business. Your opinions are less and less interesting, but it's at a stage where people get more and more keen to transmit their opinions. The boredom of that is desperate. I’ll volunteer or go and listen to young children reading, anything other than not being useful.”

Her four children – three daughters and a son – with her ex-husband, Matthew Rice, who designed some of Emma Bridgewater’s most well-loved animal and plant prints, are now all older than she was when she started the business. “It was a flying start, and it was a bit of lucky timing that the idea came along when I was gloriously unfettered at 23 – it's jolly hard to think of new plans later on in life.”

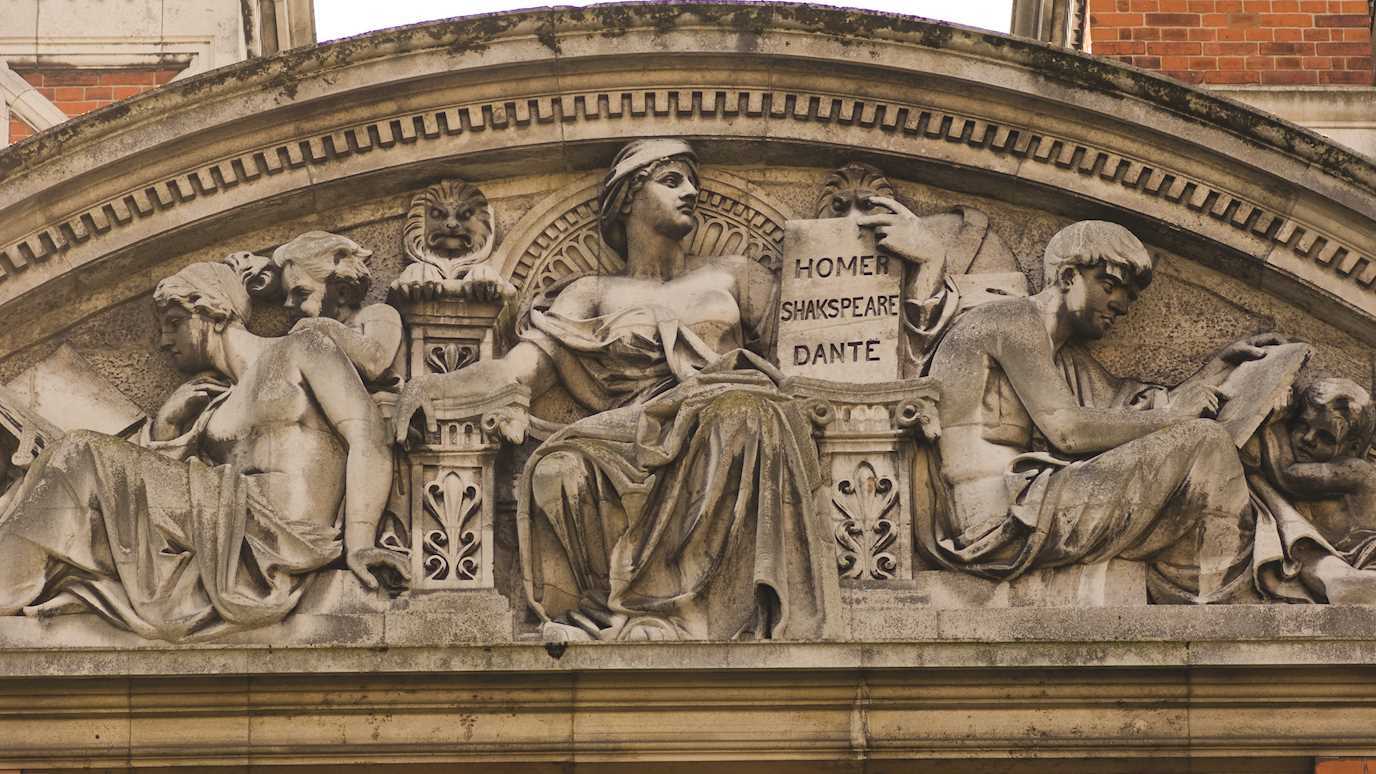

Dame Emma had only recently graduated from Bedford College, where she read English Literature. “Reading English Literature at Bedford in the early 80s was lovely; it was a huge privilege to be in Regent's Park. The course was big and rangy, and we worked prodigiously,” she says. “I think that my wordiness is hugely central to the business. I've approached design in words – I can describe what I want, what I'm doing, and I can talk about it in an evocative way, and I think that that's one hundred per cent down to my education.”

She credits her maternal grandfather, a clergyman and Cambridge graduate, with her passion for learning for learning’s sake. “He took a clear position that your education is for your life, not just to set you up for a job. If you go to university, you must study a subject that you love because it is the foundation that will characterise your life,” she says.

It’s no surprise, then, that her advice to students now is to “study the thing that they are passionate about, rather than something that they think is going to earn them lots of money. I want so much for everybody who goes to university to have three years of exploring the world and making friends.”

What does she think of AI and automation’s ever-increasing ubiquity and potential threat to traditional jobs and manufacturing? “AI is clearly capable of doing marvellous things, for example in medical diagnostics, and I’m not immune to its charms – but it also could be terrible for people and I'm sure there's going to be a massive exit of skills,” she says. “But it is up to each of us to make decisions for ourselves; you can become completely helpless and dependent, or you can decide to hang on to your skills and keep on saying ‘people matter.’”

Craft – whether on an individual basis or in a bustling factory – is more important than ever, she says. “We should all do more making – it's fundamental to the kind of creatures we are. We need to put our effort into making something useful; that feels vital to me.”