“Studying the human brain is such a privilege" - Meet Narender Ramnani, Professor of Neuroscience.

The sheer number of connections in the brain far exceeds the number of stars in our galaxy. “The human brain is endlessly fascinating and studying it is such a privilege” says Professor Narender Ramnani. His research focuses on understanding the brain’s organisation, but his commitment goes beyond science—he is deeply engaged in promoting inclusive research cultures and tackling structural inequalities in higher education, such as the causes of awarding gaps.

What do you research and why does it matter?

I lead a research programme that studies large-scale brain systems—particularly those connecting the frontal lobes with the cerebellum. Frontal lobe systems play critical roles in solving new and unfamiliar problems, making decisions, and translating them into actions, that help us learn and adapt. The cerebellum, often thought of as the brain’s “autopilot,” contains most of the brain’s neurons. It learns from the frontal lobe and, over a lifetime, stores a vast repository of mental and movement-related habits.

The workings of the healthy brain are fascinating. That knowledge underpins vital work on conditions like stroke and Parkinson’s disease, as well as healthy ageing.

How do you carry out your research?

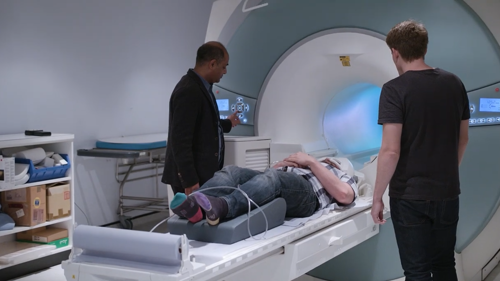

We use functional MRI in two main ways. First, resting-state scans, where participants lie still in the scanner, allow us to record spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity. When activity patterns across different areas are related, it suggests those areas are connected in a network. These experiments reveal the brain’s wiring and help us map its networks.

Second, we study plasticity—the brain’s ability to change and store information. Using functional MRI, we measure where and how activity changes, for example, we give people being scanned a puzzle to solve, which will then show us what happens in the brain when they learn a new habit.

Tell us more about a current project you’re excited about?

We’re exploring how different areas in the cerebellum communicate with the rest of the brain. We’ve worked out how different parts of the frontal lobe connect with the cerebellum, and more recently mapped the connections of over 400 parts of the cerebellum with about 170,000 locations elsewhere in the brain. We’ve used scans from 500 participants to create a complex map that reveals patterns of communication.

The emerging connectivity patterns are both fascinating and beautiful.

This work also addresses a broader challenge: the replication crisis in science, where many findings fail to replicate. We take research credibility seriously and want to ensure that the anatomical atlases we generate can be trusted. We have worked out which connections replicate across two matched groups, and which do not. Of course, there are limits to replicability - some replicability failures are likely due to natural biological variation between people.

How do you bring your neuroscience research into the classroom?

I teach and coordinate a course on Clinical and Cognitive Neuroscience in which students learn about the healthy brain, what can go wrong in it, and how our understanding of the brain helps clinicians to devise treatments about certain conditions. For example, it’s possible to use deep-brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease to ‘switch off’ certain brain areas, and in doing so, restore balance in brain circuits that become disordered by the disease.

It’s amazing to watch symptoms just disappear as soon as the stimulation is turned on.

I also bring survivors of stroke and Parkinson’s disease into my lectures, so students can hear directly about their lived experience, finding out how it’s affected their lives and what a difference the treatment strategies have made. It adds a human touch to their learning and really makes it come alive.

What's a surprising aspect of your work?

We question everything—even long-standing assumptions. Models typically used to detect brain activity in thousands of experiments make certain assumptions, but our research has uncovered that some important aspects of those models are basically wrong! We’ve also shown that those assumptions can’t be general to everyone - they need to be age-specific to give us any hope understanding healthy ageing.

How do you use your research skills to help improve society?

Two areas matter deeply to me:

Universities must become more equitable. Data still show barriers that prevent some groups from accessing higher education or thriving once there. I analyse student data to test for these systemic barriers and use the results to inform strategies to remove them. I’ve also investigated patterns of exclusion in UK research culture, including the ethnic composition of decision-making committees in UKRI Research Councils—work that has prompted action to tackle under-representation. I hold internal and external roles in these areas, including Vice Dean for EDI and member of the Race Equality Charter Governance Committee. In January 2026, I step into the role of Associate Dean for Culture and Inclusion in the new Science Faculty.

A second area relates to science policy. Decisions about the future of UK science need to be informed by a proper understanding of research. I serve on the advisory group for the Parliamentary and Scientific Committee All-Party Parliamentary Group, connecting scientists with parliamentarians. It’s a two-way street: we help them understand science so they can shape effective policies that support it. I’ve also contributed to Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology briefings on topics like brain–machine interfaces.

What do you hope to do in your new role as President of the British Neuroscience Association (BNA)?

The BNA’s mission is to inform, influence, and connect. We keep neuroscientists up to date on the latest research and policy, run major events like the Festival of Neuroscience, and build connections between the BNA and other learned societies, academia, industry, and the public. We’re working on promoting the interests of UK neuroscientists and encouraging good scientific practices such as those that address the replicability crisis mentioned earlier and ensuring that policy decisions are informed by the voices of neuroscientists.

As President, I’m committed to improving conditions for early-career researchers—listening to their concerns and strengthening the ecosystem that supports their careers. EDI is central to everything we do. We’ve revamped governance to make the BNA fit for the future: new structures, new committees, and new ways of working. For example, I’ve established a BNA EDI Advisory Board to oversee our inclusion work, ask tough questions about diversity and culture in UK neuroscience, and develop practical solutions.

Final fun question, can you sum up Royal Holloway in three words?

There are too many! I can do it in four – it would have to be. . . Friendly. Supportive. Open. Innovative.

Discover more about our Department of Psychology via the links below or return to our Research in Focus homepage.