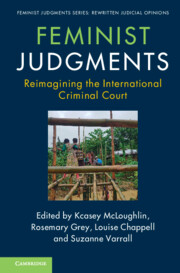

Professor Jill Marshall’s reimagining of a judgment from the International Criminal Court on Afghanistan has been published open access within Feminist Judgments at the International Criminal Court eds CUP (2025)

The book is divided into different sections and Feminist Reimagining of Select Judgments and Decisions. Professor Marshall separately reimagines a decision by the ICC on Afghanistan as part of five legal issues at the ICC in relation to thatcountry, namely: (1) the notion of gender-based persecution by the Taliban in the Pre-Trial Chamber’s decision to open an investigation into Afghanistan; (2) the jurisdiction test; (3) the gravity test; (4) the complementarity test; and (5) the interests of justice test. In line with the feminist methodology used for this volume, the authors were asked to write their contributions as if they were ICC judges.

As the editors of the volume explain, and what follows is taken from their reflection, the five legal issues chosen are all central to the ICC’s engagement on Afghanistan from 2007 to 2020. Importantly, however, all the issues pre-date the August 2021 Taliban takeover of Afghanistan. Consequently, the authors are reimagining ICC decisions adopted when the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, backed by US and other international forces, was fighting the Taliban and other non-state armed groups, not at the time when the Republic has fallen, US forces have left the country, and the Taliban has become the de facto government.

Judge Jill Marshall: The ‘Gravity’ Test in Afghanistan

There are different tests which the ICC Prosecutor must establish regarding alledge crimes. One of these is that the alleged crimes meet the ‘gravity threshold’ to be authorised to open an investigation. In its actual 2019 decision, the Pre-Trial Chamber of the ICC ruled that war crimes and crimes against humanity allegedly committed by the Afghan army and the Taliban within Afghanistan, and by American forces against Afghan detainees, were sufficiently serious to pass this ‘gravity threshold’. In her decision, ‘Judge Marshall’ (as Professor Marshall had to become in her writing, reimagines the ‘gravity threshold’ through a gender lens.

Specifically, Judge Marshall guides the reader through the ICC’s assessment of the gravity of the crimes by all parties to the conflict. The assessment focuses on the scale, nature, manner, and impact of the violations. In contrast to the original decision, Judge Marshall’s decision includes a gender analysis to assess both how the violations have been committed, and what they mean in the context of the Afghan conflict and the discrimination, deprivation, and trauma that they have caused in this situation. This analysis is further strengthened by Judge Marshall in the impact section, underlining the importance of recognising the consequences of living with the experiences of the violations in the broader context of the conflict.

In explicating her decision, Marshall also reflects on the challenge of using feminist analysis while remaining within the limits of what the ICC and legal rules prescribe.

Feminism in law, Judge Marshall notes, ‘makes use of the power that law holds, whilst resisting that same power’. Navigating this paradox is not an easy task; it demands making the most of law, without falling into the trap of reproducing patriarchal structures that view Afghan women mainly as victims. Judge Marshall manages this but her judgment points to the balancing act underlying the exercise of feminist reimagination in itself.

The text is open access and available here https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/feminist-judgments-reimagining-the-international-criminal-court/BACAA982919FB4081C44C63D3B39F672